Expedition Art

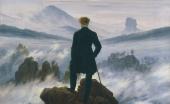

The exhibition »Expedition Art« examines the interaction of art and the natural sciences, as illustrated by landscape painting around 1800. In doing so it aims to make a contribution towards the redefinition of Romanticism – in a museum whose great strength lies in the painting of the Romantic Movement (Caspar David Friedrich, Philipp Otto Runge). Since the mid-18th century, close links had formed between natural scientists and landscape painters. New developments in the empirical natural sciences provided a completely new basis for people’s relationship to nature. This had important consequences in terms of the artistic treatment of landscape; the preoccupation with nature, both as a complex system and as a study of specific details, brought with it a rapid expansion in new landscape aspects. However it also had an effect on they way in which nature was perceived. Artists could now combine direct observation of nature with the newly acquired knowledge of relations within nature and their evolution.

Science

The sciences of geology/mineralogy, botany and meteorology were of particular importance for landscape painting. In the second half of the 18th century geology became the leading science, extending by means of empirical research the traditional model of explaining the world based on Christian belief.

Landscape painting placed increasing emphasis on the exact depiction of geological structures, mountain forms and different types of rock such as granite or basalt. This was also connected to matters of contemporary discourse, such as the vulcanism/neptunism debate or the dispute surrounding the formation of basalt. Artists such as Johan Christian Dahl, Thomas Ender among others absorbed the theories expressed in contemporary publications and based their paintings on a geological view of landscape. The Swiss artists Caspar Wolf and Samuel Birmann developed a new artistic vocabulary to enable them to depict ice, huge glaciers and mountain formations in the correct proportions.

As a theory of the formation of the earth, geognosy also had an influential effect on artists. Its ideas were reflected in the mountain views of Caspar David Friedrich and the landscapes of Carl Gustav Carus. Carus invented the ‘Erdlebenbildkunst’ (his term for the depiction of the earth’s life) in which scientific knowledge was to form the basis of art. Alexander von Humboldt’s aesthetic concept was very close to this; he urged artists to depict the geographically specific nature of a particular landscape’s vegetation. Here, too, the precise scientific observation of nature was raised to the level of an ideal for landscape painters.

Around 1800, ephemeral phenomena such as light, air and clouds also became subject to this ‘scientific treatment’. A number of artists, among them John Constable and Johan Christian Dahl, undertook meteorological observations and captured their impressions in cloud studies.

Artists explored particular geographical regions in search of specific motifs, which they captured in the form of sketches, studies, watercolours and paintings. This ‘search’ required them to travel, initially within their local surroundings, as seen in the work of Caspar David Friedrich, but later also to distant lands, as with Moritz Rugendas, who followed in the footsteps of Humboldt in his travels across America.