Contents

- Portraits of Friedrich

- Friedrich’s experimental approach in the early years

- The Rügen experience

- The early oil paintings

- religious and political significance

- The overpowering forces of nature

- Friedrich’s Rückenfiguren

- Seascapes and fishermen

- Nature Studies

- Clouds, fog, light and the play of colours

- Friedrich’s influence

- The late work

- Contemporary Image Receptions

Tour of the exhibition

Caspar David Friedrich is a key figure in Romantic art. With his atmospheric and memorable paintings, he has significantly shaped our idea of this epoch. The central theme of the exhibition is the novel relationship between man and nature in his landscape depictions. In the first third of the 19th century, Friedrich provided significant impetus and turned the landscape genre into »art for a new age«. His paintings and drawings break with the traditional patterns of representation. They combine an unusually precise study of nature with a thoroughgoing will to composition. In this way, his works open up a new way of thinking about the interrelationship between subject and nature. They make us realise that man is part of nature and faces it both contemplating and thinking.

The second part of the exhibition is dedicated to the connectivity of Friedrich's works for contemporary art, especially with regard to the challenges of our time. Cross-genre and cross-media works by 21 artists enter into a dialogue with Friedrich's pictorial worlds and the ideas of nature of Romanticism.

Portraits of Friedrich

Friedrich’s outward appearance is captured in a surprisingly large number of portraits. These highly varied depictions offer a welcome opportunity to question familiar, often deeply entrenched ideas about the painter’s personality. Georg Friedrich Kersting’s famous painting of Friedrich in his studio, for example, shows him as a painstaking artist focusing on his work, while Gerhard von Kügelgen’s portrait from a few years earlier characterises him as dynamic and determined. The images created by Alphonse de Labroue and Pierre Jean David d’Angers reveal further facets of Friedrich’s personality, demonstrating that despite the explicitly anti-French statements he had made during the years of Napoleonic occupation, he was later more than willing to meet with artists from France.

Friedrich’s self-portraits reinforce the impression of openness; in these works, the painter shows himself to be a surprisingly complex and adaptable individual. This is particularly true of the early self-portrait he drew around 1800 (cat. 1), which is perhaps the strongest warning against defining Friedrich by just one aspect of his personality. The person we see here is a highly attentive and open-minded observer, who seems less interested in crafting a particular image of himself than in regarding the world around him.

Friedrich’s experimental approach in the early years

Friedrich’s experimental approach in the early years

Having begun his formal training in art with Johann Gottfried Quistorp, a drawing teacher at the University of Greifswald, Friedrich continued his studies at the Academy in Copenhagen from 1794 to 1798. Several of the watercolours he made based on excursions into the surrounding countryside demonstrate his individual approach to the depiction of English-style landscape gardens (cat. 10–13). Friedrich settled in Dresden in 1798. The direct and detailed study of nature now became central to his creative practice; the resulting drawings illustrate his strong focus on foliage and flowering plants, trees and rocks, but also situate the individual objects in their natural context (cat. 14–29). Parallel to this impressive intensification of his nature studies, Friedrich increasingly employed etching as a means of engaging with local artistic traditions in the period around 1800 (cat. 32–39). He also produced a striking group of drawings that deal with emotions ranging from sadness and melancholy to utter despair (cat. 40–47). His brother Christian produced woodcuts of selected motifs; the prints may have been intended as illustrations for a literary work, but this has not yet been identified.

The Rügen experience

In the spring of 1801, Friedrich embarked on a lengthy tour of his native region of Western Pomerania and did not return to Dresden until the following summer. He made several visits to the island of Rügen, exploring it on foot in search of interesting subject matter. Friedrich broke new ground in this way, as many of the views and vistas he captured were not yet established as artistic motifs. He appropriated and depicted what he saw in a highly objective, almost austere manner. The drawings also reveal his desire to reflect the experience of spaciousness, which he achieved above all by choosing broader perspectives and employing panoramic formats.

Numerous pencil and pen drawings provided the basis for an in-depth exploration of specific motifs. The large-format brush drawing Blick auf Arkona bei aufgehender Sonne (View of Arkona at Sunrise, cat. 51) reveals Friedrich’s talent for capturing atmospheric scenes at different times of day, while the only two gouaches to have survived from this early period (cat. 58 and 59) illustrate his subtle sense of colour. With works like these, Friedrich responded to a growing interest in images of Rügen, which was also the result of increased tourism to the island.

The early oil paintings

Friedrich’s desire to move beyond traditional patterns of perception in his depictions of nature is already evident in his early work. From 1802 onwards, he was particularly interested in exploring how landscape images could be designed to stimulate personal reflection. To this end, he not only reduced the number of potentially significant motifs in his compositions, but also left it open if and how these were to be interpreted.

When Friedrich turned to oil painting, he chose not to create topographically accurate vedute (views) or idealised landscapes with narrative staffage. Instead, he developed a form of painting that is extremely precise in terms of detail, but also thought-provoking on account of its composition and a few meaningful pictorial elements. Friedrich’s use of staffage was also innovative. The figures who appear in his paintings are not merely representatives of a larger group, such as farmers or shepherds, but are individual characters whose identity nevertheless remains unclear. These figures turn to face the landscape as engrossed observers. A leitmotif of Friedrich’s later oeuvre begins to emerge: the depiction of people contemplating nature who encourage us – the viewers of his paintings – to reflect on the very act of seeing. The staffage figures who increasingly appear in Friedrich’s works around 1810 make it apparent that he is not only depicting nature, but also presenting various manifestations of the relationship between man and nature.

religious and political significance

Friedrich also addressed the relationship between man and nature in images where human interventions have changed the landscape and endowed it with a specific meaning. The ruins of the monastery in Oybin inspired him to create several works. In his early painting Ruine Oybin (Ruins of the Oybin Monastery, cat. 70), created around 1812, the architectural elements are supplemented by a crucifix, an altar and a sculpture of the Madonna. The work is thus inviting us to reflect on questions of faith. Friedrich’s later painting Huttens Grab (Hutten’s Grave, cat. 73), on the other hand, is a reference to political debates. Here, the ruins are a monument to the humanist Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523); they also commemorate the protagonists in the Wars of Liberation which, although they brought Napoleonic rule to an end, did not – as had been hoped – lead to democratisation.

A religious meaning is alluded to in the landscapes with crosses for which Friedrich became known, but which also met with fierce opposition. In these works, the cross often appears on the central axis of a rigorously symmetrical composition, setting it apart from conventional wayside or summit crosses. Friedrich’s intention was not to seek God in nature in a pantheist sense. Rather, the religious significance derives from the abstract pictorial arrangement, which is demonstratively emphasised. The crucifix – a sculptural object that is unmistakably characterised as a human creation – serves to indicate that God can only be experienced in a highly mediated manner.

The overpowering forces of nature

The relationship between human and nature is one of the principle themes in Friedrich’s art. In the years around 1812/13, when Napoleon occupied Saxony, the painter produced a group of politically motivated images known as his patriotic pictures (cat. 85, 89 and 90). They show soldiers in the midst of a natural world experienced as a subtle menace. The figures appear to be oppressively bound in on all sides by a cave or a coniferous forest.

With his major work The Sea of Ice (cat. 95), which many contemporary viewers found unsettling, Friedrich rejected the idea of exploring nature based on any sense of superiority or the illusion that it could somehow be tamed. Inspiring this composition was the unusual formation of ice floes in the frozen Elbe River in the winter of 1820/21, which the painter had captured in oil sketches. Friedrich never travelled to regions with permanent ice cover, so that the Nordic landscapes also dating from this period were products of his imagination.

In his large-format painting of the Watzmann, its peak has a remote and inaccessible air. Although Friedrich had never seen the famous mountain in person, he succeeds here in impressively conveying its majestic dimensions. In contrast, his artist friend Carl Gustav Carus depicts the sublime glacier world of the Mont Blanc range as being within human reach by picturing two figures from behind who are standing on the precipice.

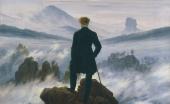

Friedrich’s Rückenfiguren

Friedrich is not the first artist to have painted Rückenfiguren – people with their backs turned to the viewer, so that their faces and the direction of their gaze are concealed. But his use of this figural type is unusually frequent and consistent. Even in images where several people are shown, the Rückenfiguren are generally depicted in silent contemplation. They are characterised as individuals through their clothing, physique and demeanour, yet their identity is not divulged. Where they come from and why they are in this landscape remains unclear.

In this way, Friedrich highlights what the Rückenfiguren are doing in the depicted moment: contemplating nature. They are often interpreted as identificatory figures, and at first glance it does seem as if Friedrich is inviting us to put ourselves in the shoes of the depicted subject. This form of identification will never be wholly successful, however. The Rückenfigur remains present in the picture and the more we try to put ourselves in their place, the more they become alien to us or even obstruct our view.

With his Rückenfiguren, Friedrich does not enable us to immerse ourselves completely in the depicted natural environment. He focuses not only on nature, but on the relationship between man and nature; above all, he emphasises the ambivalence of this relationship: like the Rückenfiguren in the paintings, we are part of nature, but our stance towards it remains that of detached observers.

Seascapes and fishermen

The sea plays a central role in Friedrich’s imagery. In the years after 1816 in particular, the painter produced numerous seascapes in which he played variations on the connection between human and nature. Focusing on the typical triad of shore, sea and sky, these works evoke an elementary experience of the natural world. The paintings often feature figures that are at home in the landscape depicted. Friedrich for example shows fishermen undertaking activities typical for the time of day represented. In some images, however, the fishermen pause in their work to contemplate and react to atmospheric panoramas in the evening and at night.

The ships shown in Friedrich’s seascapes do not always enter or leave the harbour unscathed. Shipwreck – symbolising human failure in the face of the natural forces of wind and water – is also an occasional subject. Some of the ships have for example been wrecked on the cliffs in a storm or have run aground in shallow water, leaving the crew exposed to the elements.

Finally, Friedrich’s painting Sailing Ship (cat. 119) forms an exception among his seascapes. Whereas most of the images are anchored by a strip of shore in the foreground that defines the viewer’s position in front of the picture, here we are confronted with an open sea that offers us no comparable visual foothold.

Nature Studies

The drawings that Friedrich made in nature display an impressive degree of precision. Only a few years after arriving in Dresden, he had already cultivated his drawing skills to such a degree that he was able to deftly capture a specific tree, plant or rock with their seemingly random features. It was evidently important to him to faithfully and conscientiously reproduce natural phenomena in all their individuality.

Gradually, Friedrich developed a differentiated repertoire of forms of notation that allowed him to do this particularly well by using lines, markings, abbreviations and writing to record proportions, distances and the height of his viewpoint. These notations refer not only to the innate properties of the respective trees, plants or rocks but above all to the relationship between what is depicted and the person looking at it. What Friedrich captured in his drawings is therefore not nature as such but nature as perceived by a subject. Although the studies usually do not include any figures, nature does not appear completely untouched here either. By unobtrusively yet unmistakably indicating that these scenes are tied to a perceiving subject, they always bear witness to the presence of a human being: the observer of nature.

Clouds, fog, light and the play of colours

Around 1830, Friedrich used a word in his manuscript Observations upon Viewing a Collection of Paintings that had only recently come to the fore in the field of aesthetics: mood (Stimmung). His text shows that he was thinking both about how images can trigger moods and how our own mood can influence the way we see them. The concept of mood opens up another aspect of the relationship between human and nature, because moods are neither limited to the subject alone nor are they exclusively an objective property of what is perceived.

Friedrich was singularly well equipped to bring out the atmospheric qualities in his works. His drawings, a few oil studies and many of his paintings attest to the precision and nuance with which he was able to capture natural phenomena that can evoke moods: light and shadow, the play of colours in the sky, clouds, fog and other atmospheric effects. Friedrich seems to have given a great deal of thought to how such moods could be combined with meaningful pictorial motifs, with city views as well as with trees, bushes or megalithic graves. In his Observations, he noted that it is »a great merit, perhaps the greatest thing an artist is capable of when he touches the spirit and arouses thoughts, feelings and emotions in the beholder, even if these are not his own«.

Friedrich’s influence

Caspar David Friedrich’s memorable landscapes were seminal for the field of Romantic landscape painting. In Dresden in particular, where the artist lived for four decades, his specific view of nature inspired several of his colleagues. However, although some of the artists who followed him took their cue from Friedrich’s imagery, they embraced a more realistic and less sublime approach to depicting the natural world.

The polymath Carl Gustav Carus was one of the artists under Friedrich’s sway in the 1820s. He adopted Friedrich’s figures seen from behind and also emulated the manner in which the older painter, fifteen years his senior, staged his landscapes. Ernst Ferdinand Oehme was likewise significantly influenced by Friedrich’s art but knew how to set his own accents with detailed and excerpt-like compositions. August Heinrich, a friend of Oehme’s and a student of Friedrich’s, almost obsessively scrutinised what he saw in order to depict it with an astonishing realism. With his virtuoso oil sketches of clouds, the Norwegian landscape painter Johan Christian Dahl, who was based in Dresden, revolutionised the direct reproduction of the physical world. While Friedrich only briefly took up the technique of making sketches and studies in oil, it became an integral part of the working process of both Carus and Georg Heinrich Crola.

The late work

Friedrich’s late work displays a remarkable range. The artist now revisited themes and motifs that had repeatedly preoccupied him in the decades before. After suffering a stroke on 26 June 1835, Friedrich increasingly found himself unable to paint. Instead, he focused on drawing techniques, returning to his artistic beginnings, so to speak. Numerous large-format sepia drawings demonstrate his ambitions in this medium.

While the themes of death and transience run like a leitmotif through Friedrich’s entire oeuvre, they appear with striking frequency in his final creative phase. On several occasions he chose the motif of an open grave in a cemetery, lending his rendering a symbolic charge through various meaningful objects. Mountain scenes are another subject that recurs in Friedrich’s late work. And the coastline likewise remained an important point of reference for the artist. Several of his sepia drawings show tranquil, atmospheric night-time views out at the vastness of the sea in scenes bereft of people or ships. That Friedrich was still capable of mastering large formats despite his ill health is demonstrated by his Seashore in Moonlight (cat. 197) – one of the last, if not the last painting he created.

Contemporary Image Receptions

Artworks by Caspar David Friedrich continue to inspire artists to this day. Above all Friedrich’s landscape paintings – exploring the individual and his relationship with nature – provide manifold points of reference for artistic exploration. These range from concrete image quotations to complete abstractions.

Hiroyuki Masuyama devotes himself to Friedrich’s works in a multi-layered manner: via the medium of photography, he immerses himself in Friedrich’s images at their actual places of origin or in comparable landscapes, not least to learn more about himself. He then transposes the resulting photomontages into LED light boxes, thus blurring the boundaries between reconstruction and new creation.

Olafur Eliasson, in his Colour experiment no. 86 (cat. 200), approaches the ambience of Friedrich’s images in an analytical manner: by transferring the colour spectrum of The Sea of Ice into a colour wheel, he investigates and condenses the mood of the iconic image in abstract form.

Ulrike Rosenbach revisits Friedrich’s landscape painting from a feminist perspective of the 1970s and expands it with a view to non-European cultures. In her live action Die einsame Spaziergängerin (The Lonely Walker, cat. 205), performed on a reproduction of the Mountain Landscape with Rainbow laid out on the floor, she reflects on the search for a unity of humanity and nature and positions herself in relation to the male-dominated art world.