The Chapters of the Exhibition

Narratives

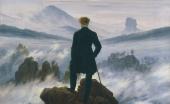

Since the earliest times, relief has been used to illustrate historical events or to convey political and religious messages. As the eye scans the three-dimensionality of the relief and explores its various levels, new perspectives on what is being depicted are also likely to arise. As demonstrated by Bertel Thorvaldsen’s three-part memorial plaque, uniformly shallow reliefs could tell a story in epic breadth. Reliefs with different heights forming a foreground, middle ground and background often alluded to different levels of time or reality – past and present, reality and memory. Artists like Jules Dalou would add dynamism to their motifs by letting them emerge from the depth of the surface. Ernst Barlach and Hermann Blumenthal, on the other hand, used the form of the “sunk relief” for their calm, contemplative contents, working their lines or figures deeply into the base. Hans Arp, on the other hand, tells a playful story in his painted and pasted relief picture: here, four cords form two heads, united in conversation

Painterly / Sculptural

In the Renaissance and Baroque eras, there was an ongoing competition between painting and sculpture as to which of the two arts was more significant and closer to reality. There was, however, a growing interest in overcoming such genre boundaries. As a result, in the 19th century painters often also worked sculpturally and sculptors painted. Relief – a medium situated between painting and sculpture all along – now became a popular playground for experimentation. Works were produced in which the figures or objects could hardly be distinguished from their base. The different levels visually merged with one another, while the motif appeared to move, to transform. Artists were now oriented towards Impressionism, along with the related interest in the moment and appearances in the alternation of light and shadow. The quick, loose brushwork of Impressionist painters was transferred to sculptural modelling. And, just like on canvas, the unfinished, incomplete was understood in relief and in full sculpture as a suitable expression for a dynamic, modern time.

Relief in Colour

Already in antiquity, sculptures and reliefs were painted for a more natural or enhanced plastic effect. When such objects were rediscovered by archaeologists in the 19th century, the artists of the time also began to design their reliefs in polychrome, meaning in several colours: some coloured the material before the actual working process began, some painted the finished object. Still others chose materials of a particular colouring, to be used individually or in combination. Sculptors such as Adolf von Hildebrand, Albert Marque or Alexander Archipenko often based their work on the colour inherent in the material; painters such as Paul Gauguin and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in turn, tended to use strong, contrasting colours in their reliefs. The French artist Henri Cros had assumed a special role: inspired by old techniques, he combined oil painting with coloured glass and wax in his works. While Cros’ ornaments still mostly served to adorn female figures, Auguste Herbin decades later celebrated the diversity of form and colour in entirely abstract wooden reliefs.

Gaze and Movement

At the beginning of the 20th century, scientific and technical developments fundamentally changed society and life in Europe. Industrialization, mass media and new means of transport influenced and shaped the cities in particular. Art responded to these changes, especially to Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity of 1905: it declared that space was always dependent on time, a “fourth dimension” alongside height, width and depth. Fascinated by this concept, artists developed works that integrated different views of objects, thus creating an impression of movement in space. Cubist artists such as Pablo Picasso sought to represent different perspectives simultaneously – on the plane of the canvas, in sculpture and also in the intermediate form of relief. Like Picasso, Alexander Archipenko and Otto Gutfreund, for example, used the special possibilities of the relief technique to link the surface with the spatial dimension in order to depict modern “simultaneity”. In this respect, they were also inspired by other forms of art, especially music: comparable to pitch and sound, shapes and colours were meant to expand within the space and recombine in one’s perception.

Conceptions of the World

Around 1900, Europe was in a state of upheaval. Science and technology had on the one hand brought progress, but on the other hand much misery. Uprisings, mass protests and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 had shaken society beyond national borders. Also the arts experienced a revolution: artists were disengaging from tradition, following their own visions, eager to shape the future. With the aim of giving the world a new order, they often relied on geometry and functionality in their works. Constructivism emerged in Russia, the Dada movement in Zurich, the De Stijl group in the Netherlands and Bauhaus in Germany. Artists were now striving for a formal and conceptual approach that could be applied to all areas of modern life. As a transitional genre between painting, sculpture and architecture, relief played a central role. Whether shaped from artistic material or developed as a collage from everyday objects: even in the smallest of formats, it appeared as the concept of a greater whole.

The Public Sphere

After the end of the Second World War, Europe lay in ruins, cities and buildings had to be rebuilt, public spaces redesigned. Numerous artists were commissioned with architecturerelated projects. In Germany – with its various occupation zones – art in public space was intended to convey new ideas and values to a population still influenced by the ideology of National Socialism. In the Soviet occupation zone and the GDR this was mainly achieved in the style of “Socialist Realism”, whereas in the rest of Germany the orientation was on the abstract art of the prewar period, regarded at the time as an internationally comprehensible “world language”. This notion was actively promoted not least by the London-based British Council. The central content of new works was always to be the human being and his role within society. British artists such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and William Turnbull had already in the 1920s approached abstraction and were designing reliefs for façades meant to be both educational and inspiring. Through the “documenta” in Kassel and other exhibitions of contemporary art, their works also became known in this country and were noticed by numerous German artists.

Space and Surrounding Space

Classical reliefs are self-contained works of art, even if they are created for specific locations and contribute to shaping their environment. In the works on display, dating from the 1930s to the 1960s, space itself becomes an integral part of the artwork – as volume, mass or void. Based on slashes and holes in the surface of the painted canvas, Lucio Fontana created a relief-like Spatial Concept series, while Lee Bontecou preferred to mould the canvas into expansive objects using steel and wire. Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp explored the relief as a wall and spatial object by superimposing layers or integrating voids and breaches. Brothers Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo enclosed the space by means of loops of metal or transparent nylon threads, while Otto Herbert Hajek formed free-standing Raumknoten (Spatial Knots) from organic forms. It seemed to make no difference whether the starting point of the work was the flat painting or the three-dimensional sculpture: the new object that emerged was a relief-like hybrid form, an interlocking of space and surface featuring unexpected new dimensions.