The Chapters of the Exhibition

Introduction

Giorgio de Chirico: Magical Reality

Vast, deserted squares, enigmatic still lifes, magically charged spaces – the pictures of Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), are as seductive and eerie, as singular and compelling as they were a century ago when they were created.

The extraordinary style developed by de Chirico between 1909 and 1919 was characterized by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) as »metaphysical« (from the Greek words metá, beyond, behind, and phýsis, nature). De Chirico’s aesthetic orientation placed him at the margins of the avant-garde movements, but he would exert a profound influence on modern art as a whole – from Surrealism to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity).

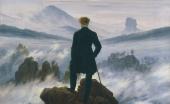

The italian artist Giorgio de Chirico was born in Greece in 1888 to a cosmopolitan family from Constantinople. He studied art in Munich from 1906 to 1909, looked very closely on German Late Romanticism. Following travels to Florence, Turin, and Milan, he spent the years 1911 to 1915 in Paris, where he encountered the cultural avant-garde. Between 1915 and 1919, after military induction, he continued to paint in the small Italian town of Ferrara.

The exhibition focuses on those decisive years of artistic upheaval occurring in de Chirico’s work between 1906 and 1919, which are contextualized in relation to their contemporary contexts. De Chirico developed his metaphysical art in a turbulent Europe marked by World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic.

In his paintings, de Chirico attempts to fathom the phenomenon of visibility. He was convinced that the spirit and the mystery of the world – given expression by ancient civilizations as myth – resided not in some imperceptible beyond, but instead in the tangible, the material world. Pivotal here was his reception of the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900).

The German philosopher’s ideas about the eternal return of the same, about »Stimmung« (meaning mood, defined by de Chirico as »atmosphere in the spiritual sense«), and about the transvaluation of values, propelled his conceptualization of motifs and compositions. And although the objects depicted in his innovative paintings and their arrangement might seem emphatically explicit, readily intelligible, they nonetheless harbour a wealth of interpretive possibilities, triggering multiple associations.

The far-reaching impact up to the present day of these images of memory, of intuition, and of apprehension foreboding was intimated already by André Breton (1896–1966), mastermind leader of the Surrealist movement:

But the paintings accomplished by de Chirico before 1918 […] have retained a unique prestige, and, judging by the gift they possess of rallying around them the least conformist minds and those most divided by opinion, it is evident that their influence remains as powerful as ever, and that their career has only just begun.

André Breton, 1941

With their deserted, sun-baked plazas, streaked with elongated shadows, so seductively expansive, yet at the same time precarious and impassable, Giorgio de Chirico’s pictures have become iconic. More than one hundred years ago, he succeeded in visualizing the impact of emptiness. Corresponding in an extraordinary way to these empty and seemingly contradictory squares, so alien to daily urban life, is a new and very real experience of space, one that emerged in 2020, as reflected as well in countless media images: for people around the world, the measures undertaken to contain the Covid-19 epidemic beginning in March 2020 have meant massive restrictions on freedom of movement and assembly.

Many of you have sent your beautiful and unsettling scenes of emptiness, photographed during this time. We are showing a growing selection here – many thanks to all of you for your submissions! You can participate up until April 10th 2021, by sending your images to: submission[at]hamburger-kunsthalle.de

The Searching Artist

DE CHIRICo AND LATE RomANtIcISm – BEFoRE AND AFtER METAPHySICAL PAINTING

Under the impression of Late Romanticism, Giorgio de Chirico lays down the foundations of his »metaphysical painting« around 1908/09 in Munich. There, he studies originals and reproductions of works by Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901) and Max Klinger (1857–1920).

He finds confirmation for his own ideas in their compositions and techniques, in their attempt to render specific atmospheres, and in their recourse to ancient mythology and its actualization: both artists combined elements drawn from diverse levels of reality with one another in such a way that unreal phenomena acquires plausibility, at the same time acquiring significance for their contemporaries.

Böcklin’s influence may have inspired Klinger to conjure the mythical beings in numerous etchings that strike us as so peculiarly evocative. He depicts centaurs, fauns, and tritons not in secluded natural settings or in the company of the gods, as is the custom among artists. In his works, they appear […] surprisingly real, they are ›natural‹.

De Chirico, 1920

Their works remind de Chirico of the fusion of myth and everyday life he experienced during his childhood in Thessaly in Greece. Step by step, and with their art as a point of departure, he develops his combinatorics, intensifying the »atmosphere« he prized so highly in Böcklin and Klinger: through their shared vision of reconciling myth with contemporary life, he formulates the aims of his own arte metafisica (metaphysical art): rather than illustrating familiar myths, he strives to create new ones.

In the wake of his metaphysical phase (1909/10–1919), as intense as it is brief, de Chirico turns again toward these two artists. Heralding this return is the Self-portrait as Odysseus (1922–1924), where the homesick hero – who has served since antiquity as a metaphor for knowledge and yearning – is borrowed from Böcklin’s image world and deployed as an expression of de Chirico’s own life journey, characterized by searching and intellectual adventure.

ATMoSPHERE, PoETRy AND thE ENIgmA oF tImE – ART AS REVELATIoN

In mid-1909, Giorgio de Chirico begins reading Friedrich Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo (1908) and Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1885). These texts profoundly unsettle both his patterns of thinking and his visual habits:

This novelty is a strange and profound poetry, infinitely mysterious and solitary, which is based on the Stimmung (I use this very effective German word which could be translated as ›atmosphere in the moral sense‹), the ›Stimmung‹, I repeat, of an autumn afternoon, when the sky is clear and the shadows are longer than in summer, for the sun is beginning to be lower.

De Chirico, 1945

The peculiar atmosphere that emanates from Nietzsche’s poetic language is a source of fascination for the young artist, as is the notion of an eternal present – a moment poised between an elusive past and a future that itself soon passes away. Through his »metaphysical painting«, he seeks in his own way to confront this enigma of time, along with other philosophical questions, among them the meaning of symbols.

Additional sources of intellectual stimulation include wide-ranging readings on the relationship between religion and art, as well as on the importance of symbols as a means of communication within tribal societies. De Chirico becomes convinced that in the modern era too, art must be »evangelical«, by which he means that it must reveal and engender the new, the unheard of.

Townscapes

tuRIN – THE BoURGEoIS AND CULTURAL IDENTITy

The early metaphysical paintings of the Parisian period (1911–1915) are associated with de Chirico’s search for identity. The deserted squares, arcades and towers, all defamiliarized views of Turin, are predicated more on emotion than on reality. The city – which de Chirico visited in 1911 when traveling to Paris – now becomes an arena of his imagination. On the one hand, Turin played an important role in his family history. On the other, Turin was the place where, 1888, Friedrich Nietzsche formulated the conceptual world so admired by de Chirico before his nervous breakdown.

Immersed in the atmosphere of an autumnal afternoon, the townscapes painted between 1912 and 1914/15 are as inviting as they are disconcerting: a fountain and a frequently reiterated arched arcade or huge towers allude to Nietzsche’s »eternal return of the same«. Their compositional clarity is deceptive: inconsistent vanishing points compel the eye to roam restlessly. Dream or reality? Everything seems filled with contradictions; the intangible evokes a yearning for the unattainable.

gREEcE – THE PoLITICAL AND CULTURAL IDENTITy

On a deserted square in »Turin«, de Chirico displays a sculpture of Ariadne, daughter of the king of Crete. According to Greek mythology, she used a thread to help the Athenian prince Theseus escape from the labyrinth of the Minotaur; here, we see her half- asleep, awaiting Dionysus’s arrival.

De Chirico refers to Nietzsche’s understanding of myth as a metaphor for knowledge and artistic creation: Ariadne is the feminine soul who discovers the secrets of the body through her marriage to Dionysus, proffering humanity a second thread. This thread leads the humans back into the labyrinth, where soul and body, man and woman, reason and the unconscious coalesce, in the process revealing the deepest truths.

Here, de Chirico introduces the idea into his metaphysical aesthetics that each work emerges from the unification of putatively feminine and masculine elements. Those elements can be symbolized by statues, but also by arcades or towers, chimneys or canons.

The placement of the Cretan princess in front of a smoking train is interpretable as a eulogy to his family’s early Greek adopted home, but also as a reference to the modernization program undertaken by liberals there, this with the approval of his father, a railway engineer.

The Loneliness of Signs

PARIS – THE CULTURAL IDENTITy

In Paris beginning in 1912/13, de Chirico not only studies the late philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, but also the works of the French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854 –1891). Beginning in late 1913, based on this foundation, he introduces the most diverse inanimate objects into his metaphysical image vocabulary. He draws these elements from history and philosophy, everyday surroundings and childhood memories. Stage managed on the picture surface in isolation from one another, they are deprived of any tangible interrelatedness.

They are pure »signs«, with no clues to their interpretation or logic or their thematic, spatial, or temporal involvements, and it is left to the viewer to develop the associative potential of these realistically painted artichokes, banana trees, and plaster casts of sculptures. In retrospect, de Chirico refers to this phenomenon – which would be taken up and further developed later by Surrealism – as the »solitudine dei segni«, the »loneliness of signs«.

DIALoGUE WITH THE PARISIAN AVANt-gARDE

Correspondences and sketchbooks document Giorgio de Chirico’s exchanges with various artists during the Parisian period. In 1913, he visits the studio of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) together with Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918). The impression made by Picasso’s early Cubist works is already perceptible in the segmented volumes of the figure of Ariadne in The Soothsayer‘s Recompense (1913); beginning in spring 1914, de Chirico intensifies his artistic dialogue with Picasso. The Spaniard, meanwhile, esteems the works of the young Italian, who he ironically dubbed »le peintre des gares« (»the painter of railway stations«).

De Chirico also discovers the Cubist works of the Ukrainian sculptor Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), whose compositions consisting of various coloured materials he views at the home of his Italian friend, the artist Alberto Magnelli (1888–1971). They influence de Chirico’s painting The Troubadour (1917), among others. Magnelli’s Man with a Hat (1914), meanwhile, is also inspired by Archipenko’s Head (1913/1957), which survives today only in cast bronze.

The Art of Clairvoyants

ART AND PoETRy AS REDEMPTIoN

»Metaphysical«, enigmatic, mysterious – these are some of the words used in 1913 by the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918) to characterize the works of Giorgio de Chirico.

Impressed by their novelty, he becomes one of the artist’s key friends and supporters. In 1914, he persuades Paul Guillaume (1891– 1934) to act as de Chirico’s art dealer.

An interest – shared by Apollinaire – in ancient Orphic secret teachings (from Orpheus, the mythical singer and poet) encourages de Chirico to develop a theory of art as redemption, as a mystical rebirth.

In 1914, in The Nostalgia of the Poet, he depicts poetry – represented by the plaster bust wearing black sunglasses of the kind worn by sightless people – as the art of clairvoyants: blind to the present day, poets like Apollinaire are capable of perceiving the past and the future with clarity. In reference to Nietzsche, who suffered a mental collapse in Turin in 1888, de Chirico is also preoccupied with the thin line separating clairvoyance from madness, a region that is fathomed by artistic creation.

HUMAN AS MANNEqUIN

Giorgio de Chirico, whose imaginative world is rooted in Greek mythology, uses a variety of paraphernalia in his artistic studies: plaster casts, goniometers, statues. The mannequin (manichino) is perhaps the most characteristic element in his metaphysical pictures, and a hybrid figure – because the extremities are replaced by objects – that is set in a perspectivally deceptive picture space. Beginning in 1914, he develops their shaping unceasingly – paralleling events in his own biography.

The first mannequins appear as wooden wig stands bearing dotted lines of the kind made with tailor’s chalk. De Chirico relates the activity of the tailor to the sculptors of antiquity, who calculated the ideal proportions of the human body.

The props that appear together with the mannequins, which are staged in an increasingly independent fashion, underscore the lifeless character of these dolls – analogous auxiliaries were once used in fashioning effigies of the dead. At eye level, finally, many of the manichini wear ribbons decorated with circles or stars: these refer to ancient rites of initiation – rituals involving acceptance into certain groups – and endow the faceless heads with a cryptic aura.

IN THE CHILD’S BRAIN

In 1920, passing the display window of the Galerie Paul Guillaume in Paris, André Breton (1896–1966) catches sight of de Chirico’s painting The Revenant (1914). The arresting strangeness of this work administers such an aesthetic shock that he immediately disembarks from his bus: he simply must own the work. The founder of Surrealism will keep this painting – which will acquire a fetish character for the entire group, and will later be renamed The Child’s Brain by the French writer Louis Aragon (1897–1982) – until the end of his life. The painting forms the beginning of the Surrealist appreciation of de Chirico’s metaphysical imagery, and at the same time its reception by a number of artists – from Picasso to Max Ernst.

The closed eyes of the depicted male figure refer again to the imagination of the clairvoyant artist, who experiences revelation in a half-sleep or wake dream. The yellow book that lies before him is suggested by de Chirico’s French edition of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1912).

In 1928, with this work as a point of departure, Breton develops his Surrealist interpretation of the »visionary painter«, who creates art out of revelation, and cites de Chirico’s own words:

In particular, it is a question of liberating art from everything that involves it in the already familiar, all objects, everything remembered, all symbols must be cast aside. […] The revelation that a work of art engenders in us […] must be so powerful within us, must fills us with such joy or such pain that we are compelled to paint […].

De Chirico cited by André Breton, 1928

Arte metafisica

thE SoNgS oF hALF-DEAth

Depth, enigma, dream, and revelation are key terms for both Giorgio de Chirico and his brother Alberto Andrea de Chirico (1891–1952). In 1909/10, still inspired formally by Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901), he depicts him as a solitary artist in the landscape of his homeland of Thessaly in northern Greece, confronting the riddle of the world.

Beginning in 1909, the two brothers jointly develop the idea of a metaphysical art (arte metafisica), a term designed to identify a mode of thought and experience that transcends the boundaries separating painting, literature and music.

Alberto de Chirico’s musical gifts reveal themselves early. In 1906, he studies composition in Munich with Max Reger (1873–1916). Giorgio de Chirico attends these lessons as a translator, and views reproductions of works by Böcklin found in Reger’s collection .

Alberto de Chirico’s compositions are characterized by apparently disjointed, disharmonious tones and sounds. In 1914, under the stage name Savinio, he gives a performance in Paris of the work Les chants de la mi-mort (The Songs of Half-Death), which combines music, literature, theatre and stage design. His title alludes to the ideas of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) concerning perceptual experience that occurs between waking and dreaming. It is a condition of wake dreams which is also central for Giorgio de Chirico‘s concept of the revelation.

The Metaphysics of Things

A WoRLD BEyoND SENSE AND LoGIC

Emerging in Ferrara in early 1915 is a radical thematic and iconographic shift in the work of Giorgio de Chirico. Now, he flees the horror of war, taking refuge in the material microcosm of everyday life. Themes such as yearning and melancholy lose their infinite dimension. With a seemingly cold, clinical gaze, he analyses animate and inanimate material, discovering here too – in a »metaphysics of ordinary things« – a world beyond logic and sense.

Foreshortened perspectives condense the paintings and drawings; accumulating now are geography maps, picture frames, typically Ferrarese pastries, insignia and signal flags. Becoming apparent in the process is not just de Chirico’s fondness for combining unrelated items, one that dates already from the Parisian years (1911-1915). The amalgamation in a confined space of props related to the civil and military worlds also manifests a desire for the security of enclosed spaces, for inner order and ingathering.

THE PICTURE WITHIN A PICTURE

During the Ferrarese years (1915–1918), Giorgio de Chirico repeatedly paints pictures within pictures. They appear in the midst of vertiginous perspectives, aggregates of goniometers, measuring tools, and metaphysical interiors characterized by moulding strips. Configured in the framed pictures to begin with are everyday objects such as pastries and maps.

Beginning in 1916, he integrates realistic depictions of landscapes or buildings found in the immediate vicinity. Metaphysical Interior with Large Factory (1916), for example, contains a view of a nearby factory, which de Chirico borrowed from a postcard. These geometric compositions challenge the viewer regarding perceptual distinctions between interior and exterior spaces.

METAPHySICAL STILL LIFES

During World War I (1914–1918), Giorgio de Chirico intensifies his search for an »evangelical« message for art, one oriented toward the future: its mission is to reveal the unknown. With the painting Sacred Fish, executed in late 1918 in the wake of his wartime experiences, his recovery from the Spanish flu, and his sorrow over the death of his friend Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), he takes up an early Christian symbol of salvation and rebirth. In this metaphysical still life, de Chirico arranges objects with an emphasis on the contrast between their realistic mode of depiction and their peculiar configuration: reality now penetrates into an iconographic system that is grounded in unreality.

WIt is this quality that makes such works a stimulus to both Surrealist artists in France and exponents of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) tendency in Germany.

The Spread of Metaphysics

Carlo Carrà

In spring of 1917, the Italian Futurist Carlo Carrà (1881–1966) and Giorgio de Chirico meet by chance in Ferrara. Both become patients at the Villa del Seminario, a military hospital that treats traumatized soldiers. For a period of four months, they work together side-by-side. The two incorporate the objects that surround them into their metaphysical works: surgical instruments, prostheses for maimed soldiers, mannequins, turned objects from the workshops, and paraphernalia for leisure time hobbies.

De Chirico and Carrà develop an interpretation of the war from the perspective of those who suffer its consequences, bringing to light an existence between two extremes: a brutal war and daily life in the hospital.

Later, Carrà will rework his paintings in an attempt to soften the impact of de Chirico’s undeniable influence. This becomes particularly evident in the evolution of his mannequin figures: he heightens their emotional impact through their greater affinity with living beings.

Giorgio Morandi

During World War I, the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964) – who is promptly discharged from military service due to dizzy spells – works primarily as a drawing instructor. In late 1918, having moved beyond his Cubo-Futurist phase, he reorients his gaze by studying works (initially in reproduction) by Carlo Carrà (1881–1966) and Giorgio de Chirico, and launches his initial experimentation with metaphysical imagery.

Turned wooden bars, carpentry templates, bottles and vessels appear in his works as well. While de Chirico often uses such items as surrogates, Morandi presents them as objects in their own right. Their impact is no less unsettling in the townscape-style configurations of these etched and painted still lifes. Also their continuously evolving coloristic sobriety make Morandi one of the great still life painters of the 20th century – not least of all through his intensely individual interpretation of the metaphysical art of de Chirico and the remarkable, groundbreaking conception of space, which appears simultaneously empty and solid which de Chirico had developed in his early townscapes.

The Searching Artist

DE CHIRICo’S RETURN To MAx KLINGER

With the Mysterious Baths (Bagni misteriosi), produced beginning in 1934, long after the close of his metaphysical phase, de Chirico creates a series that is as poetic as it is disquieting. Rising through the water’s surface are bathing cabins and mysterious swimmers. Populating the scene alongside visitors in ordinary bourgeois attire are mythological beings such as centaurs (hybrid of man and horse) and sea gods.

The ten lithographs of the series Mythologie (1934) illustrate a text by Jean Cocteau (1889–1963). These images are permeated with reminiscences of the public baths de Chirico visited with his father as a child, along with allusions to classical mythology, whose poetic power and sense of fantasy shaped his youth in Thessaly in Greece. At the same time, de Chirico returns here again to Max Klinger (1857–1920), whom he regards as »the modern artist par excellence« as late as 1920, and who served as an essential point of departure for the development of his metaphysical painting. During the 1930s, in his search for a link between the real and the fantastical, de Chirico again strengthens Klinger’s amalgamation of antiquity and modernity.