Familiar Yet Unknown

To celebrate a large donation, the Kunsthalle is presenting a selection of distinguished works by the Hamburg artist Friedrich Einhoff (b. 1936) that provides an overview of his rich oeuvre. Einhoff has been one of the foremost figures on Hamburg’s art scene ever since the 1960s, both as a painter and draughtsman and as a seminal teacher of younger artists at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences. His works using a wide variety of techniques always revolve around the human figure with its ambivalent and fragile nature. Einhoff’s figures appear individually or in groups, their alienated faces merging with their surroundings.

The Hamburger Kunsthalle has had the good fortune of being able to make a representative selection of over 50 important works from Einhoff’s studio. Private funding has enabled their acquisition by the Prints and Drawings department, where, together with an existing collection of Einhoff’s early drawings, they now constitute a cohort of more than 70 works from all phases of the artist’s career.

Themes of the Exhibition

Figures and Places

In his early works, Friedrich Einhoff depicted individual figures or groups undergoing medical treatments or in swimming pools. The compact, in some cases vaguely limned bodies are shown bathing or standing under the shower. The interiors are sober and cool, reduced to just a few details. The figures meld with the surrounding water and even seem to be trapped in it. In these threatening scenarios, Einhoff was expressing a subtle critique of state institutions such as sanatoriums, which he depicts as places of loneliness and anxiety. The motifs suggest that no care or healing can be expected here.

Figure and Object

The figures seen here are playfully furnished with a variety of objects that merge with their bodies like prostheses. One figure has wings, but doesn’t use them to take flight, and others are given a stick as an extension of their arms, thus becoming stick figures. Sometimes a tube is attached to a mouth or a corset supports the body. The message is that humans are dependent on outside assistance and that they make use of the world of things for this purpose. With low-key humour, Einhoff suggests the ambivalence in the relationship between human and object: medical devices compensate for deficits in the human body and yet at the same time they create dependencies, so that in the end the human being surrenders to things and becomes, for example, a stick figure.

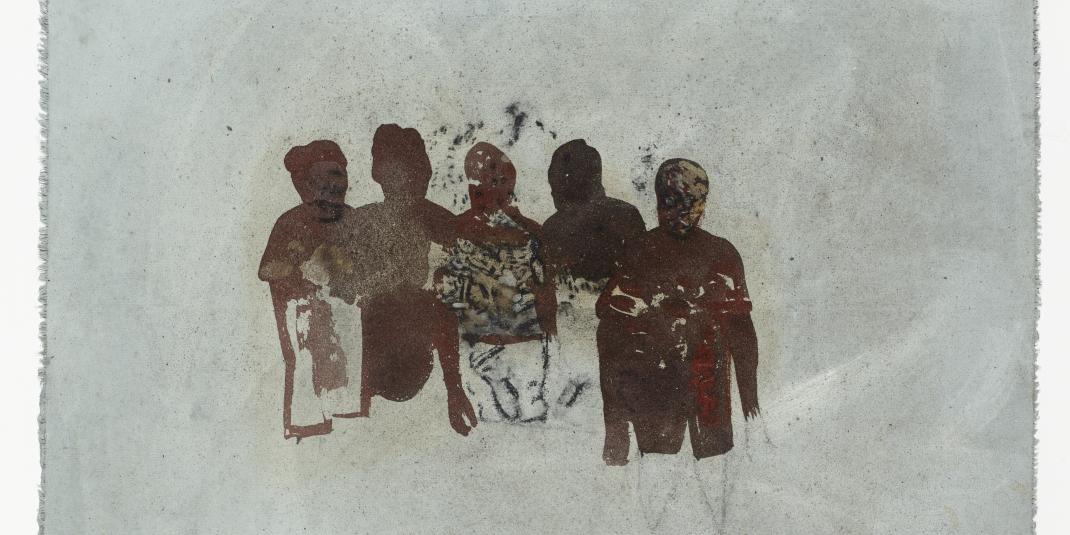

Groups of Figures

The grouped figures, rendered unrecognisable, meld together to become an indistinguishable mass. Some of them look in the same direction, for example the school class pictured frontally, or they pose as if in a group photo. The adumbrated bodies are so close that they touch one another. It seems as though nothing separates them. Neither facial expressions nor gestures provide any clues to individual identity or emotions. The individual blends into the anonymous group as a mere element of the whole. Einhoff’s groups of figures give the impression of a close-knit community. And yet the figures do not interact with each other. Each remains alone, a shadowy, faceless being within the group.

Moments of Dissolution

In Einhoff’s pictures, the figure in the landscape, whether bathing in a lake or knee-deep in the earth, melds with the elements of nature. The silhouettes of the figures dissolve, the bodies indistinguishable from their surroundings. They remain present only as a trace, like a faded negative or blurred photo. The landscape setting is unspecific. Shapes and colours merge, causing the figures to melt into the elements of water and earth. The figures are covered by soil applied on top of the paint; they are buried by it. The circle of life closes. Einhoff places humanity in the context of the natural elements, with water and earth playing a fundamental role in his images. These motifs speak of the transience of life.

Alienation

Einhoff made use of various methods to alienate the human form. He for example painted over groups of figures with discrete brushstrokes in lighter or darker shades to render them unrecognisable. The heads are only hinted at and the group picture resembles an underexposed photograph with bright colour accents. Einhoff worked in parallel in photography with over- and underexposures, so that the faces of his subjects are not identifiable. Another alienation effect is the rendering of multiple heads in Einhoff’s drawings. The heads are faceless or they remain but fragments, not representing any true physiognomies. Einhoff’s heads connote a rejection of portrait painting, seeming to propose an alternative. The silhouettes stand in contrast to the heads’ blank facelessness, emphasising the vacuum. The head as a vessel is filled with abstract ideas and thoughts. Einhoff’s heads thus symbolise both material emptiness and immaterial abundance.