Contents

Anita Rée

Anita Rée is one of the most fascinating and enigmatic artist of the 1920s. In many respects she lived a life in between worlds: as an independent woman in an art world on the verge between tradition and Modernism, as a regional artist with international aspirations, as a native from Hamburg brought up as a Protestant, with South American and Jewish roots. The works of Anita Rée (1885–1933) also reflect the at times radical changes in modern society at the beginning of the 20th century. Yet their main focus lies on the search for one’s own identity that is still highly topical and existential.

In hauntingly intense paintings, Rée depicts both people of different origins and the self as a foreign being. Her intimate female nudes continue to touch us today. Portraits of society gentlemen, the southern landscape as a place of yearning, worldly figure paintings with religious overtones or lone animals in stark dunes mirror the wide variety of her motives. This first comprehensive exhibition on the artist features around 200 paintings, watercolours, drawings and designed objects, some of them unknown until now. The show presents a surprisingly multi-faceted oeuvre, ranging from Impressionistic plein-air studies, to Cubist Mediterranean landscapes all the way to New Objectivity portraits.

Exhibition tour

Introduction

Anita Rée (1885–1933) has been represented within the collection of the Hamburger Kunsthalle for more than a century but has never been honoured with a solo show. This first comprehensive museum exhibition of the artist finally sheds light on a major, multifaceted oeuvre, which spans from Impressionist paintings, through Mediterranean landscapes, to New Objectivist portraiture.

Anita Rée, born 1885 in Hamburg, as second daughter of Eduard Israel Rée and Anna Clara, took painting lessons with Arthur Siebelist in Hittfeld between 1904 and 1910, continued her studies in Paris during the winter of 1912/13 and workedin Positano, in Southern Italy, from 1922 to 1925. Back in Hamburg, she received national recognition through numerous portrait and public commissions, and made valuable connections within the art world. She spent her final years in seclusion on the island of Sylt where she took her life in December 1933.

Anita Ree in der Malklasse von Arthur Siebelist in Hittfeld, nach 1904, Archiv Maike Bruhns, Hamburg © Hamburger Kunsthalle

Early Works

In 1904, Anita Rée joined the painting school of Arthur Siebelist. Presumably until 1910, she painted Impressionist pictures flooded with light alongside other students, including Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann and Franz Nölken. She followed new developments in art through galleries, private collections, periodicals and books, and was particularly interested in the works of Paul Cézanne, André Derain and Paula Modersohn-Becker. A stay in Paris during the winter of 1912/13 intensified these impressions. Rée occupied herself with the key features of modern art: the free handling of colour and form, as well as the rendering of space on a flat canvas. Rée’s images document her fascination with the Other, with what is foreign, as exemplified by various portraits of a Chinese man and a dark-skinned girl. Children on the cusp of puberty fascinated Rée. She captured their awkward movements, blunt candour and their inwardly directed gazes. With such figure paintings, Anita Rée established herself as an artist. She was invited to participate in exhibitions, and her work entered collections. Rée networked with art collectors and intellectuals, and in 1919 became a member of the newly founded Hamburg Secession. She had made a good start.

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Junger Chinese, um 1913, Ol auf Leinwand, 75,5 x 60,5 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

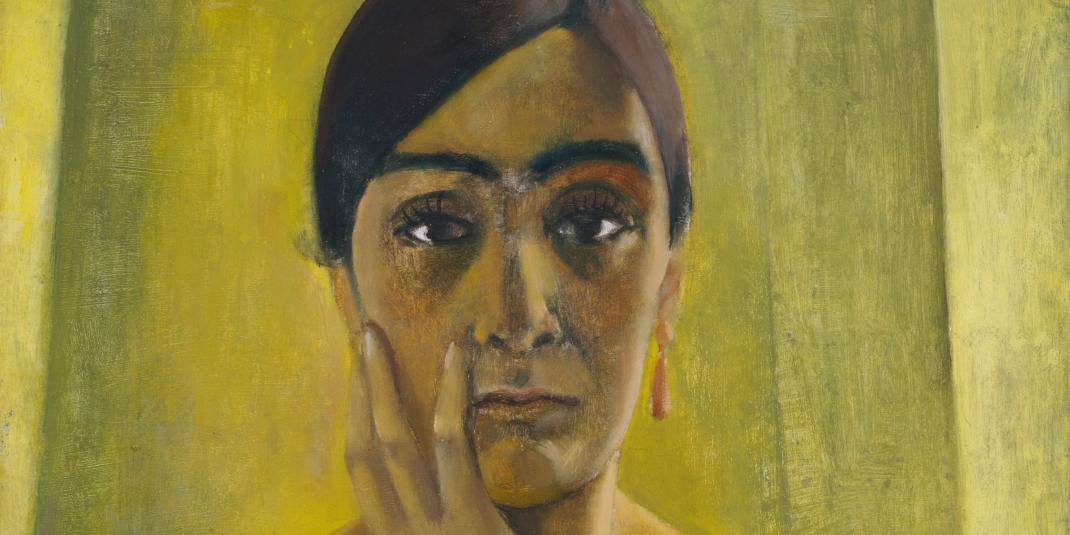

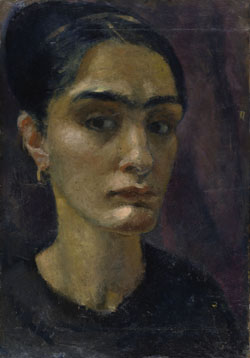

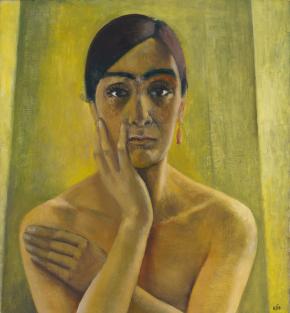

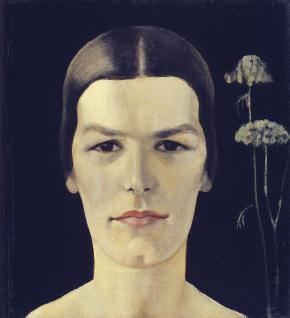

Self-portraits

In an early self-portrait from 1904, Anita Rée already gazes directly at herself and the viewer, as if to ask: “Who am I?” Throughout her entire oeuvre, she explored her own being, and she used the entire potential of colour, form and composition to give expression to her inner world. Rée still took pains at the beginning of her career to achieve an exact representation of her own likeness. Inspired by artists such as Paul Cézanne and Fernand Léger, she concentrated increasingly on the intrinsic value of form and colour, and began to experiment. Anita Rée was concerned with the question of identity and origins. In numerous self-portraits, she emphasised her exotic appearance. In the dark Self-Portrait on Pantelleria (Room 3), she merges her own figure with the South Italian landscape.

(l) Anita Rée (1885–1933): Selbstbildnis, um 1911, Öl auf Holz, 42 x 29,5 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

(r) Anita Rée (1885–1933): Selbstbildnis in Hittfeld, 1904, Öl auf Leinwand, auf Sperrholz aufgezogen, 41 x 46 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

Places of Longing

At the age of thirty-five, Anita Rée had become firmly established in the Hamburg art scene and also experienced her first national success. She was now drawn towards the South. On the one hand, she wanted to experience the grand museums and collections; on the other, she was in search of more diverse landscapes for her art.

In the early summer of 1921, Anita Rée travelled to Tyrol, where she stayed in Grins, a village perched on a plateau at the foot of the Lechtal Alps. In paintings reminiscent of those by Paul Cézanne of Montagne Sainte-Victoire, she captured rocky massifs, gorges and mountain peaks in prismatic forms of colour. She was also interested in the inhabitants of this landscape and their buildings, which conformed to the valleys or nestled against the slopes.

In August 1922, Rée crossed the Alps and travelled as far as Southern Italy. The fishing village Positano, on the Amalfi Coast, remained her base for three years. From here, she undertook trips to Naples, Rome, Assisi, Florence and Ravenna, to Calabria, the Island of Sicily and Pantelleria. Rée’s views of Positano differ from the Romantic nineteenth-century images of Italy. She focused fully on the site’s location, between the sea and the mountain slopes, on cube-shaped groups of houses and looming towers, steep stairs and narrow alleys, as well as the many branches of walnut and olive trees. Pallid colour tones often lend the village a ghostly appearance, like theatrical scenery.

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Schlucht bei Pians, 1921, Öl auf Leinwand, 80 x 61,5 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Weiße Nussbäume, 1922 – 1925, Öl auf Leinwand, 71,2 x 80,3 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

Familiar Strangers

The Amalfi Coast was a popular destination in the 1920s, particularly among German writers and painters. Anita Rée found new artist colleagues in Positano, including Carlo Mense and Richard Seewald. Since she spoke Italian fluently, she easily made contacts among the locals as well, and she painted and drew numerous village residents.

She emphasised the individuality of her models but also developed specific types, especially an androgynous, ovular facial structure which she would frequently reuse. The painting Couple (Two Roman Heads) is a good example of how Rée was inspired by the art of the Early Renaissance, especially the works of Piero della Francesca. She cites his clear colours, sharp contours, precise details and the sculptural poses of his figures.

In November 1925, Anita Rée returned home. Positano had become too confining for her, she had money worries, and as a foreigner, she would have sensed the growing nationalism. In January 1926, she was already able to exhibit her new works in Hamburg, which won extensive recognition as well as providing her with numerous commissions for portraits. Although she only travelled one more time to Positano years later, her Italian experience had a long-lasting effect.

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Paar (Zwei römische Köpfe), 1922 – 1925, Öl auf Leinwand, 51 x 45,5 cm, Privatbesitz USA © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Christoph Irrgang

Distant Paradises

Anita Rée was fascinated by the cultures of the Ancient World – of Europe, Africa and Asia – and engaged intensely with their pictorial traditions. In Hamburg, the Ethnographic Museum and the Museum of Art and Design provided her with stimuli. Rée was also friends with the Hamburg-born art historian Aby Warburg and regularly used his interdisciplinary and transnational library of cultural studies.

Around 1930, Rée’s interests led her to unusual work. In three paintings, she merged mythical animals, flowers, and landscapes into a fantastical world. On three wardrobes, she painted monkeys and parrots against a golden background and surrounded them with ornamental designs. Freed from her own high demands upon herself and art, she could lose herself while dabbling in painting her own fantasy worlds, drawing upon her inner store of images.

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Zwei Fabeltiere, um 1931, Öl auf Leinwand, 52 x 112,5 cm Privatbesitz © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Christoph Irrgang

Worldly and Sacred

Anita Rée’s murals where not her first works to address Christian motifs. Rather, she began to engage with such themes ten years earlier in drawings and paintings. She seldom linked her depictions explicitly to religion, usually striking a balance between the worldly and the sacred. Her interest in Christian motifs was associated with her appreciation of the Old Masters. She was particularly enthusiastic about images of the Madonna. In several works, Rée referenced biblical stories such as the Flight into Egypt. In the painting Woman in Blue, the path leads through a modern, urban world. Rée used blue – the colour of melancholia, faith and fidelity – not only for clothing; she also surrounded her figures with deep-blue backgrounds or azure halos.

Anita Rée portrayed Bertha, the maid of the Wriedt merchant family and one of her favourite models, in numerous pictures. Here, she appears as a nun with a thorny thistle and as a lady in the style of the Early Renaissance, within a baroque church frame. Once again, world and faith were joined in Rée’s art.

Anita Rée (1885–1933): Blaue Frau, vor 1919, Öl auf Leinwand, 90 x 69 cm Privatbesitz© Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Christoph Irrgang

Portraits of Gentlemen and Images of Women

Anita Rée caused a sensation at the beginning of 1926 when she exhibitedher works from Italy. In the period that followed, she received numerous commissions for portraits but also executed portraits of people she cherished. Rée generally depicted men in imposing paintings reflecting their occupations and social standing. Such is the case for the director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle Gustav Pauli and the literary historian Albert Malte Wagner. Books and sculptures attest to the intellectual and cultivated natures of those represented. In drawings, Rée found a more personal approach to her models and captured their individual characteristics by deliberately utilising the visual effects of the artistic medium. While Rée tended to caricature her male models, she reacted more sensitively to the female ones. She did not represent women such as Valerie Alport and Magdalena Scharlach, who were friends and sponsors for Rée, as influential art patrons but rather as individuals.

(l) Anita Rée (1885–1933): Bildnis Otto Pauly, um 1927, Öl auf Leinwand, 64,5 x 49,2 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

(r) Anita Rée (1885–1933): Bildnis Hildegard Heise, 1927, Öl auf Leinwand, 40,6 x 35,6 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Elke Walford

Final Works

Although she was recognised as an artist, Anita Rée felt increasingly uneasy in Hamburg. Among the reasons were the economic crisis and the growing strength of the National Socialists, but also personal disappointments. In the late summer of 1932, she left the city and moved to the island of Sylt. The change in location was accompanied by a change in medium, style and subject. On Sylt, Anita Rée worked almost exclusively in watercolour. She freed herself from the factual, detailed composition of previous years and now translated what she saw directly into a picture. Rée only painted a small number of portraits. The island landscape became her new subject, in which she saw the reflection of her deep solitude. She found her own pictorial language for the sparse, wintery environment, reduced the colour palette of the dunes to only a few tones and gave their soft forms bodily shapes. She banished people altogether from these images and instead populated the landscapes with animals.

Although Anita Rée consistently lamented her inability to work, she was actually highly productive on Sylt. She again found her way to new artistic expression, allowing nature to become the mirror of her feelings.

(l) Anita Ree auf Sylt, 1932/33

(r) Anita Rée (1885–1933): Leuchtturm mit Zaun und Meer,1932/33, Aquarell, 39,9 x 49 cm, Privatbesitz© Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Christoph Irrgang

Audioguide

| Description | Audio |

|---|---|

| Self-Portrait, 1930 | |

| Mythical creatures, 1931 | |

| White Nuttrees, 1922–1925 |

Supported by