Contents

The Light of the Campagna

Claude Gellée (1604/05–1682), who is known as Claude Lorrain or simply Claude, was one of the most important landscape artists of the 17th century. Although he was born in France, Claude spent most of his life in Rome. As a painter and draughtsman, he developed a concept of ideal landscape that continued to influence landscape painters internationally until well into the 19th century.

The exhibition in the Hubertus Wald Forum presents 90 pen and brush drawings by Claude Lorrain from the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum in London. Most of the works have come from the prestigious collections of Sir Richard Payne Knight and the Dukes of Devonshire. These highly impressive drawings range from freely executed nature studies done on sketching expeditions in the Roman Campagna to preparatory designs for paintings, and also include a selection of works from the Liber Veritatis, an album of masterful drawings the artist made in order to record the compositions of his finished paintings.

Claude’s drawings are supplemented by 20 of his etchings from the holdings of the Kupferstichkabinett (Department of Prints and Drawings) and selected examples of the 300 etchings with mezzotint that were produced in the late 18th century by the Englishman Richard Earlom after drawings by Claude.

In addition to the Lorrain exhibition, we will be showing a Horst Janssen exhibition from our own collections until January 14, 2018 with the title Horst Janssen. Hommage à Claude in the Harzen-Cabinet.

Exhibition Tour

Introduction

Anonymer Künstler nach Richard Collin und Joachim von Sandrart; Bildnis Claude Lorrain, nach 1674, Feder in Grau, grau laviert, weiß gehöht, Spuren von Graphit,

auf blauem Papier, 144 x 120 mm (oval), von hinten montiert in einen Bogen Papier, 265 x 323 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

The painter and draughtsman Claude Gellée, named Claude Lorrain (1600 or 1604/05–1682) was born in Lorraine but lived and worked most of his life in Rome. He is one of the most significant artists of the 17th century and his idealized landscapes continued to influence international landscape painting well into the mid-19th century.

Not so well known in Germany, however, is the fact that Claude was also an outstanding draughtsman. The Light of the Campagna aims to explore this fascinating aspect of Claude’s oeuvre with a selection of 90 pen and brush drawings. The exhibits are on loan from the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum in London, which is home to the largest and best collection of Claude’s drawings worldwide, comprising more than 500 works. The 90 drawings were specially chosen for the exhibition and will only be on display at the Kunsthalle. This is the first time that the artist’s drawings will be presented on this scale in Germany.

Rome and Environs

Das Grabmal der Cecilia Metella an der Via Appia Antica, um 1638, Feder und Pinsel in Braun, grau laviert, Graphit, Einfassungslinie (Feder in Braun; beschnitten), 285 x 221 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

After moving to Rome permanently in 1627, Claude Lorrain began to sketch the city and the surrounding countryside, the Roman Campagna. About 1200 drawings have survived, including a considerable number of studies of identifiable landscapes and buildings. One of Claude’s favoured subjects was the dome of St Peter’s, though the majority of drawings depict ancient Roman ruins such as the triumphal arches and temples of the Forum and Colosseum. Beyond the walls of Rome, he explored the countryside on foot, studying such monuments as the Tomb of Cecilia Metella on the Via Appia and the Ponte Molle with particular interest. Impressive drawings of the Temple of the Sibyl and the waterfalls of Tivoli in the mountains to the northeast also survived. Although he was fastidious about drawing from direct observation, Claude did not generally aim to create a faithful rendering of what he saw in front of him – his meticulous studies were mostly used as a source of material and motifs for his paintings of idealized landscapes.

Views of the Landscape

Der Lago Bracciano mit Blick auf den Monte Soratte, rechts ein stehender Hirte mit Ziegen unter einer Baumgruppe, um 1660–1665 Schwarze Kreide, Feder in Braun, braun und grau laviert, Einfassungslinie (Graphit, beschnitten), 166 x 243 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

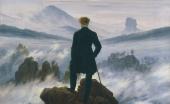

On his excursions to the countryside, Claude Lorrain drew many sweeping views, radiating harmony and tranquillity, of the seemingly endless, undulating landscape. He first filled in the backgrounds and middle ground of his compositions, often drawn directly from nature, initially leaving the foreground free of subjects. Trees and rocky outcrops were then added to the foreground in the studio, usually with a pen and dark-coloured ink or wash. In combination with his seated or standing repoussoir figures, frequently positioned with their backs to the viewer, they lead our gaze into the landscape stretched out before us, heightening the sense of depth in the picture. A particularly good example of Claude’s method is offered by the stage-like composition of the view of Lago Bracciano with Monte Soratte in the distance,.Drawn with black chalk, the view is flanked in the foreground on the right by a large tree and a herdsman with goats.

Trees and Forests

Landschaft mit großem Baum, zwei Wanderern und einem Gebäude in der Ferne, um 1650, Graphit, Pinsel in Grau und Ocker, im Himmel und in den Figuren weiß gehöht, auf hell ockerfarben grundiertem Papier, 257 x 403 mm, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Claude Lorrain focussed almost exclusively on landscapes in his drawings, more than any other European artist before him. Hundreds of his surviving works portray the rich diversity of nature in its many different forms. Trees were by far the most frequent subject of his works. Considering that trees are as vital to a landscape painter as figures are to a painter of religious or historical subjects. They must have truly fascinated him and his works seem like a tribute to their splendour, diversity and beauty. Claude portrayed his trees as if they were living characters, while at the same time showing little interest in their botanical details. His landscape drawings were not intended to be scientifically accurate depictions of natural forms but rather strove to capture a special atmosphere or mood. Such moments could be found at any time of day, but Claude seemed to be particularly drawn to the hours of dusk and dawn.

Light and Shadow

Baumgruppe, um 1640, Feder und Pinsel in Braun und Dunkelbraun,, Farbspuren in Grau, Fragment einer Einfassungslinie (Feder in Braun), 259 x 240 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

One of Claude Lorrain’s primary interests was to capture the effects of the changing light throughout the course of the day. Of particular note in this context are a number of drawings that were mostly or entirely executed with a brush and brown ink. The small group comprises about 15 brush drawings that were made between 1635 and 1645. Claude managed to create a graduated, wash effect using a wet brush, and simultaneously left certain areas of the white paper blank to give the illusion of light. As a result, these works have been aptly described as »monochrome watercolours«. Almost all of the drawings show his inclination towards simplification and abstraction. It is thus hardly surprising that Claude’s techniques have been compared with the East Asian art of ink-wash painting. These modern and creative studies are undeniably among the artist’s best and are masterpieces of European landscape drawing.

Ships and Seaports

Hafenszene mit Palast und großem Segelschiff, um 1638, Feder und Pinsel in Braun, grau laviert, Einfassungslinie (Feder in Braun), 195 x 263 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Ships and seaports also feature in Claude Lorrain’s body of drawings. He sought out such motifs on occasion in Rome and in the coastal town Civitavecchia. Claude was generally more interested in the buildings and the ships and boats anchored in the harbour than in the workers and sailors.

He mostly drew imaginative scenes with lavish palaces and an impressive assortment of vessels. In the centre, the rippling surface of the seawater in the wake of a passing ship or boat glistens in the light of the sun as it sets or rises in the vast sky. These compositions were mostly based on studies in perspective that required Claude to follow strict rules, unlike his drawings from nature. All of the mentioned port scenes are imbued with a sense of peace and tranquillity. Claude seldom portrayed the dangers of sea travel. There are several scenes of storms from the early phase of his artistic career in which he used his virtuoso drawing techniques to full effect.

Ideal Landscapes

Ideallandschaft mit Brücke und Reiter und dem Tempel der Sibylle in Tivoli bei Sonnenuntergang, um 1642, Feder und Pinsel in Braun, grau laviert, 196 x 264 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Claude Lorrain’s artistic achievements were a milestone in the history of landscape painting that inspired countless artists over the following centuries. His ideal landscapes combine the various elements of a landscape in such a balanced, harmonious way, it is easy to forget that this portrayal of nature is a figment of the artist’s imagination. Claude’s carefully drawn studies from nature – be they of trees and forests, ancient buildings or panoramic views of the Campagna – provided the basic material for his compositions. Such places of lore as the famed Tivoli with its waterfalls and the Temple of the Sibyl offered a wealth of motifs that were often incorporated into his paintings. One variation of the ideal landscape is the pastoral, which portrays the timeless serenity of untamed nature untouched by civilization.

The drawings in the Liber Veritatis (»Book of Truth«) are copies of Claude’s paintings. To achieve the desired effects, the artist used different drawing techniques, such as pen and ink, brush drawing, different coloured washes and heightening in white to create nuances, for example, in the foliage in the foreground and background.

Landscapes with Christian Motifs

Landschaft mit der Verstoßung Hagars und Ismaels durch Abraham, um 1668, Feder und Pinsel in Braun, weiß gehöht, 195 x 256 mm, London, © The Trustees of the British Museum

A much sought-after painter, Claude Lorrain received numerous commissions from high-ranking members of the clergy and the nobility. His paintings were often conceived as pendants, comprising, for instance, a morning and an evening scene or a scene of a harbour paired with an inland vista. His pictorial inventions were particularly valued because his landscapes did not merely serve as a background for biblical scenes. Claude managed to seamlessly combine both, imbuing his landscapes with a narrative quality that reflected the underlying tone of the story: Landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, the subject of many different works, shows the Holy Family taking shelter in an idyllic landscape. In contrast, the flickering light in Landscape with the Martyrdom of Saint Catherine underscores the dramatic event unfolding in the scene. Even in his depictions of stories from the Bible and the lives of the saints, Claude chose to portray specific moments that allowed him to pursue his interest in capturing atmospheric phenomena, such as the harbour scenes with their sophisticated backlighting.

Mythological Landscapes

links: Claude Gellée, gen. Lorrain (1600 - 1682), Aeneas und Dido in Karthago, 120 x 149,2 cm, Öl auf Leinwand, © Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk, Foto: Elke Walford

rechts: Richard Earlom (1743 - 1822), Stecher, nach Claude Gellée, gen. Lorrain (1600 - 1682), Aeneas und Dido in Karthago / "A Sea View, with Buildings and many Figures", In: "Liber Veritatis", Band II, London 1777, Blatt 186, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Bibliothek, © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Foto: Christoph Irrgang

Claude Lorrain similarly used his landscapes as a setting for mythological subjects, which were regarded as the highest genre in the arts along with depictions of biblical history. Virgil’s stories of the adventures of Aeneas, the father of Rome, were a popular literary source. Yet in his drawings and paintings, Claude often does not make it clear whether he is illustrating a specific episode or just referencing the overall story. A much-lauded trait of Claude’s works is his ability to imbue his landscapes with an emotional atmosphere, which may be related to personal experience, too: although the mythological tales seem to be set in faraway times, they – if one believes the stories – occurred in the same places that Claude and his contemporaries regularly visited and that the artist studied.

The painting “Aeneas and Dido in Carthage”, the drawing after the painting from the Liber Veritatis and the mezzotint by Richard Earlom after the drawing are presented here together, showing how the colours and light effects of the landscape vary in the different media despite all having the same subject matter.

Supported by