HAMBURG SCHOOL

The Hamburger Kunsthalle invites you to discover the fascinating world of the 19th century from the vantage point of the »Hamburg School«. The exhibition looks at the arts in 19th-century Hamburg and the fortunes of the artists active in the city. Some 120 paintings, drawings and works of graphic art, including a number of major works by the featured artists, will offer a representative overview of an entire century of artistic practice in Hamburg.

Since Hamburg had no art academy, aspiring painters had to travel elsewhere to do their training and perfect their technical skills. Prime destinations for Hamburg artists included the art academies in Copenhagen, Dresden, Munich and Düsseldorf. At the same time, horizons were opening up for them to the north and south, with study trips to Scandinavia and Italy exerting a lasting influence. The exhibition examines the artists' productive encounters with these places and shows how the new experiences continued to have an impact on their work even after their return to the Hanseatic city.

Featured are the main protagonists on Hamburg's art scene over the course of an entire century, alongside artists who spent significant parts of their career in the city, among them Philipp Otto Runge, Erwin Speckter, Jacob Gensler, Valentin Ruths and Thomas Herbst. The show spans an arc from works produced around 1800 under the sway of Classicism and Romanticism, to realistic tendencies starting in the 1820s, culminating in the gradual emergence of the avant-garde in the last third of the 19th century, represented by examples of Naturalism, Impressionism and Art Nouveau. Alongside the more established artists, many figures will be brought to light who have been unjustly forgotten.

The exhibition is a cooperative project with the Art History Seminar at the University of Hamburg on the occasion of a double anniversary: 2019 marks 150 years since the founding of the Kunsthalle as well as the university’s centenary.

Supported by: Hubertus Wald Stiftung, Philipp Otto Runge Stiftung and Ministry of Culture and Media Hamburg

Media Partner: Hamburger Abendblatt

Culture Partner: NDR Kultur

Topics of the exhibition

Under the Spell of the Arabesque – On the Influence and Reception of Philipp Otto Runge

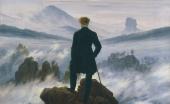

After stays in Hamburg, Copenhagen and Dresden, Philipp Otto Runge returned to live in the Hanseatic City from 1804 until his early death in 1810. It was he who, together with Caspar David Friedrich, had introduced the art of Early Romanticism. Also in his late works, Runge had adhered to the structural means of the romantic arabesque as his essential formal principle. Characteristic in this context are depictions consisting of an inner image and frame composition. Both image levels are interrelated in terms of their content.

In Hamburg Runge’s artistic activities fell on fertile ground. Several artists of the following generation drew inspiration from his image worlds, and yet, in the process, they would also modify his multifaceted and highly complex world of ideas. After Runge’s demise, it was particularly his brother Daniel who secured the artist’s intellectual and artistic legacy, and likewise initiated its distribution. Various copies after his paintings bear witness to the specific rank Runge held with respect to the development of art of his times.

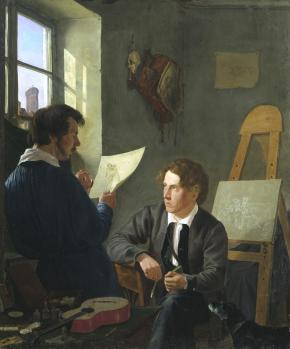

The View into the Mirror and at Friends. A School Starting to Form

Artists in the studio, in front of the canvas, engaged in discussion, observing themselves and their fellow painters: the different variants in which the Hamburg painters created portraits of each other are exceptionally diverse. Some of these works were developed in other places: as Hamburg was lacking an academy, Munich was one of the places where many artists met again during their studies. Away from home, renewing old acquaintances was particularly important in order to feel part of a community and thus better equipped to deal with the many new impressions. Here, the construction of a shared identity can be traced particularly well, this is also reflected in the personal reports on joint activities in the evening and the constitution of a group based on the use of Low German. As a final result there are even pictures of the dead friends: Louis Asher, who portrayed his close companion Erwin Speckter on the death bed, and Hans Speckter, who in turn made a drawing of his teacher Asher – impressive attestations of friendships between Hamburg artists spanning generations.

Religion and Drama. About Historical Painting in Hamburg

At the turn of the 20th, Hamburg was a city where music and drama had its firm place. Not least as it was Gotthold Ephraim Lessing who had formerly worked as a dramatist at the Hamburg National Theatre. Shakespeare’s Hamlet and King Lear belonged to the regular repertoire at the theatre at the Gänsemarkt square. The situation for painting was somewhat different: since the city did not have a royal court, there were also no substantial, representative commissions in this field. In view of the predominantly Protestant faith, the demand for altar pieces was also relatively low. For this reason, one finds large-format works with depictions from classical literature or the Bible only occasionally. However, based on the painters’ education at the academies of Düsseldorf, Munich and Paris, these works certainly complied with the requirements of contemporary historical painting. In addition, there exist a considerable number of small, delicate watercolours featuring Christian themes oriented on the most prominent representative of Nazarene painting, Friedrich Overbeck.

Identity or »Home«. Hamburg and its Surroundings

Hamburg was a popular object of study for painters, who nonetheless all pursued quite different aims with their paintings. The artists’ views onto their own city since the years around 1800 also differed significantly from those in the mid-18th century. If formerly an idealized form of depiction oriented on older painting traditions was customary, there now increasingly manifested a desire to develop more individual perspectives and intimate ways of seeing one’s home city. In these views onto Hamburg, for instance, the church towers which usually make the Hanseatic city so recognizable, were merely scantly rendered. They were considered of minor importance compared to an intensive study of the landscape, sky and horizon. The city was experienced and illustrated in a new way: gently embedded in an enchanting nature or surrounded by a forest that impressed with its fertility and unspoiled appeal. Yet also paintings focussing on the inner city convey rather diverse images of Hamburg: as an early industrial harbour city geared towards state-of-the-art telecommunications and maritime trade or as a city offering picturesque walkways in well-tended landscape gardens.

Conscious of Loss. Hamburg Artists as Chroniclers of Impermanence

After the demolition of the medieval dome in the years 1804 to 1806, the citizens of Hamburg could witness a gradual decline of many old, well-familiar urban structures. The St. Johns Church, for instance, was torn down in 1829. During this period the artists had an important role to play by capturing what they observed: they documented their city’s demolition and deterioration in lithographs and paintings, thus laying down a significant artistic marker against it. Several among them, for example Carl Julius Milde and Martin Gensler, even temporarily gave up painting, in order to devote their skills to the improvement and preservation of endangered or dilapidated buildings under monument protection. The inner-city old town of Hamburg was deteriorating more and more, before the Great Fire destroyed almost everything in 1842.

Blankenese – A fishermen’s village is discovered artistically

In the course of the 19th century, the fishermen’s village Blankenese situated at the Lower Elbe River outside the gates of Hamburg was gradually explored by the artists active in the Hanseatic city. As it appears from the various portrayals, it was regarded as an attractive painting site particularly during the 1830s and 1840s, owing above all to its picturesque location. Located on the banks of the Elbe river, parts of Blankenese stretched up the Geesthang, with the fishermen’s houses nestled on its hillsides. Scenic perspectives were plentiful – and they still are today.

During their study excursions the artists had the impression of being on a journey through time. Coming directly from working in the bustling trade metropolis, the contrast to the simple, natural way of life of the fishermen and their families was striking. Before this backdrop, it is understandable that the artists not only focused on impressions of the beach, but also studied and portrayed the fishermen’s families, including their modest houses and traditional clothing, their crafts and everyday practices.

The Alps – more than just a milestone

A number of Hamburg artists headed for Munich during the first decades of the 19th century to enroll at the city’s art academy. But it was actually Mother Nature that offered a true place of study to those landscape and genre painters from northern Germany. They were particularly enchanted by the Alps which served as an inexhaustible source of visual stimulation. Captivated, on the one hand, by bizarre rock formations, dense mountainous forests, valleys carved deep into landscapes and nearly impassable trails which were often only used by mountain farmers and smugglers, they also derived inspiration from the local population with their traditional attire and customs. The impressions they captured are not only remarkable in an artistic sense, they also provide a historical glimpse at the specific culture of the alpine region.

Let’s Go North. The Fascination of Scandinavia

In view of the fact that an art academy did not yet exist in Hamburg, ambitious young artists had no other choice than to seek out educational institutions elsewhere. Next to Dresden and Munich, it was the academy in Copenhagen that was very attractive to Northern German artists during the first half of the 19th century. Already Caspar David Friedrich and Philipp Otto Runge had studied at this establishment, which was considered as particularly progressive and liberal. Various protagonists of the Hamburger Schule followed in their footsteps from the early 1830s on.

With Copenhagen as a basis, several students from Hamburg also ceased the opportunity of departing on study trips to Sweden and especially to Norway. An inspiring example for this was the Norwegian landscape Johan Christian Dahl who lived in Dresden. Dahl had travelled to his home country in 1826 and achieved great success with his depictions of the spectacular Norwegian landscape. Soon after, the Hamburg artists tried to equal him. Christian Morgenstern followed in Dahl’s tracks in 1827, Louis Gurlitt traveled to Norway in 1832 and 1835, and Hermann Kauffmann in 1843. Once there, they were not only fascinated with Scandinavia’s sublime nature, but also with the local population who seemed to be living in harmony with it.

Coastal Fascination. From the Probstei to Helgoland

In addition to Helgoland, Germany’s only deep-sea island, the Probstei was one of the most popular attractions for Hamburg’s artists during the 19th century. That strip of land stretching eastward from the Bay of Kiel – with its miles of sandy beaches and scattered fishing villages – conveys the picture of a primal landscape as yet untouched by the rapid expansion of industrialization. Painters like Jacob Gensler and Hermann Kauffmann didn’t only focus on the impressive natural setting, they also rendered realistic portraits of the locals and their surroundings. Some of Hamburg’s artists also experienced the elemental forces of nature on Helgoland and the neighbouring island of Düne.

Land of Expectations, Hamburg Painters Pilgrimage to Italy

For Hamburg’s artists in the 19th century, the trip to Italy frequently marked the culmination of their artistic training. Italy’s idyllic mountains and coasts, the remnants of ancient Roman culture and the Italian Renaissance as well as the pleasant Mediterranean climate inspired countless artists to set out for the south. This Italian infatuation began with Johann Joachim Faber, the first of Hamburg’s artists to tour Italy from 1806 to 1808 and again from 1816 to 1827, and it stretched all the way to Ascan Lutteroth, who discovered Italy’s charms in the 1860s and 1870s. The artists captured the dramatic landscapes plein air in their innumerable oil studies which they often later used for large-scale studio paintings. In addition to their enthusiasm for landscapes, Hamburg’s artists also showed a particular interest in the local population with their curiously alien traditions and customs.

For the Love of Art. Art Patrons and Institutions

Founded as early as 1765, Hamburg’s Patriotische Gesellschaft (Patriotic Society) had a productive impact on the advancement of the arts with its drawing schools. In the early 19th century, the process of institutionalizing social policies with civic participation was continued. Hamburg’s Kunstverein (Art Association), whose beginnings date back to 1817, didn’t just actively promote the local production of contemporary art, it also fostered a communal awareness and appreciation of museums in the Hanseatic city by helping to compile collections of works. The Hamburger Künstlerverein (Hamburg Artists Association), which was established in 1832 and included the leading exponents of the Hamburg School, created a forum for the productive exchange of artistic matters and, at the same time, further contributed to making this topic a mainstay of city life. As a result, art-minded citizens were encouraged to donate their own collections, and in 1850 the first public picture gallery was opened in the Börsenarkaden (Stock Exchange Arcade). Additional foundations and gifts followed suit. So the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which was founded in 1869, is the visible tribute to the process of civic participation.

Off to Pastures New. Paths out of Hamburg

Also in the last third of the 19th century, the absence of a local art academy had caused various Hamburg artists to leave their home city. Some of them had begun their studies at the local school of arts and crafts and learned their first steps partly from representatives of the “classical” generation of the Hamburg School, for instance, the brothers Günther and Martin Gensler or Louis Asher. Coming from a different period, they were, however, no longer able to instruct these students in the modern, progressive trends emerging at the time. This is why the more ambitious artists would move to other places, preferably the art academies of Weimar, Munich and Düsseldorf, offering a wide range of possibilities for further training. Some of them succeeded in becoming established and settling there. At the time, the structures Hamburg provided in this regard were limited and thus not suited to bind its native artists in the long term.

The Avant-garde on Site. The Hamburg Artists Club 1897

In 1897, the Hamburg artists Julius von Ehren, Ernst Eitner, Thomas Herbst, Arthur Illies, Paul Kayser, Friedrich Schaper, Arthur Siebelist und Julius Wohlers joined forces and founded the Hamburgische Künstlerclub (Hamburg Artists Club). This meant that the Hanseatic city now prided itself in having one of the first artist associations in Germany, a year before the Berlin Secession was established. The club members had been inspired to take that step by Alfred Lichtwark, the director of Hamburger Kunsthalle, who pursued the plan to establish the avant-garde in that north German centre of trade and recruit them to paint Hamburg motifs.

At first, the representatives of the Künstlerclub provoked a negative response in Hamburg with their intensely colourful paintings, influenced, in part, by a preoccupation with French Impressionism. But Lichtwark expressed his support and purchased their works for the Kunsthalle to be exhibited in the Sammlung von Bildern aus Hamburg (Collection of Pictures from Hamburg). However, as a result of his extensive pressure on the members’ artistic production, their relationship cooled down around the turn of the century. And the Hamburgische Künstlerclub was denied a resounding success. In 1907, the club held one last exhibition, then disbanded the same year. The next programmatic association of Hamburg artists was to be the Hamburger Sezession (Hamburg Secession) which was founded in 1919.