Contents

Nature Unleashed

In a large-scale exhibition spanning several epochs, the Hamburger Kunsthalle traces based on important works how artists working in different media picture natural catastrophes while also shedding light on humanity’s failure to come to terms with nature due, among other things, of our faith in technology. »Nature Unleashed: The Image of Catastrophe since 1600« features approximately 120 exhibits, including paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, photographs, films and videos. As viewers make their way past blazing fires, earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions and sinking ships, they will take note of pictorial constants in the expression of such disasters but will also become aware of the differences in depiction from one era to the next. The show’s special appeal lies in the close juxtaposition of artworks created centuries apart. The trajectory of exhibited works spans an arc from the years around 1600 to the present day. Contemporary works serve to anchor the theme in the here and now and underline its topicality.

Catastrophes are omnipresent. The media constantly reports on natural disasters, acts of war, political upheavals and other crisis scenarios, characterising them all with the common term »catastrophe«. Catastrophes don’t just happen, they are made. It is only in our perception, in our active engagement with such drastic events that they take on distinctive contours and reveal their typical face. Every age makes its own catastrophes and redefines the criteria by which certain events are labelled as such. These fundamental observations form the basis for the exhibition project.

Alongside pieces from the Hamburger Kunsthalle’s own collections, important works were loaned by prestigious museums and collections including the Musée du Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the National Gallery, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Kunsthaus Zurich.

A richly illustrated catalogue will accompany the exhibition in which all works on view are presented with individual commentaries. Catalogue essays contributed by experts on this complex topic set it against the backdrop of current catastrophe research.

The exhibition is a cooperative project between the Hamburger Kunsthalle and the Chair of Art History and Visual Culture Studies at the University of Passau.

Supported by: Freunde der Kunsthalle e. V., Ministry of Culture and Media Hamburg, Malschule in der Kunsthalle e.V and Hamburger Feuerkasse Versicherungs-AG

Media Partner: Hamburger Abendblatt

Culture Partner: NDR Kultur

With works by

Nicolai Abilgaard (1743–1809), Andreas Achenbach (1815–1910), Jan Asselijn (um 1610 – 1652), Félix Auvray (1800–1833), Jakob Becker (1810–1872), Oscar Begas (1828–1883),Josef Bergler d. J. (1753–1829), Hermann Biow (1803–1850), Julius von Bismarck (*1983), Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), Franz Ludwig Catel (1778–1856), Henri-Guillaume Chatillon (1780–1856), Johan Christian Dahl (1788–1857), Henri-Pierre Danloux (1753–1809), Auguste Desperret (1804–1865), Christoph Draeger (*1965), Elger Esser (*1967), Kota Ezawa (*1969), Pietro Fabris (tätig 1740–1792), Maso Finiguerra (1426–1464), John Flaxman (1755–1826), Giovanni Battista Franco (1510 – um 1561), Caspar David Friedrich (1774 –1840), Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741–1825), Oliviero Gatti (1579–1648), Jacob Gensler (1808–1845), Martin Gensler (1811–1881), Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), James Gillray (1757–1815), Alexis-Francois Girard (1787–1870), Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson (1767–1824), Filippo Giuntotardi (1767–1831), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617), Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem (1562–1638), Jakob Philipp Hackert (1737–1807), August Haun (1815–1894), Daniel van Heil (1604–1664), Marikke Heinz-Hoek (*1944), Wenzel Hollar (1607–1677), Eugène Isabey (1803–1886), Christian Jankowski (*1968), Rudolf Jordan (1810–1887), Hermann Kauffmann d. Ä. (1808–1889), Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997), Ferdinand Kobell (1740–1799), Thomas Kohl (*1960), Jacques-Philippe Lebas (1707–1783), Héctor Leroux (1829–1900), Carl Friedrich Lessing (1808–1880), William Lodge (1649–1689), Melchior Lorck (1526/27 – nach 1583), Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740–1812), Caspar Luyken (1672–1708), Bernhard Martin (*1966), John Martin (1789–1854), Johan Mayr (Lebensdaten unbekannt), Felix Meyer (1653–1713), Johann Georg Meyer (1813–1886), Mime Misu (1888–1953), Aert van der Neer (1603/04–1677), Marcel Odenbach (*1953), Olphaert den Otter (*1955), August Pezzey d. J. (1875–1904), Bartolomeo Pinelli (1781–1835), Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), Tommaso Piroli (um 1750/52 – 1824), Egbert Lievensz. van der Poel (1621–1664), Friedrich Preller (1804–1878), Josef Carl Berthold Püttner (1821–1881), Johann Heinrich Ramberg (1763–1840), Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754–1829), Hubert Robert (1733–1808), Friedrich von Rohde (Lebensdaten unbekannt), Charles Roß (1816–1858), Francesco Rosselli (1445 – vor 1513), Aloys Rump (*1949), Jean-Pierre Saint-Ours (1752–1809), Karin Sander(*1957), Christian Friedrich Scheib (1737–1810), Hans-Christian Schink (*1961), Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794–1872), Uta Schotten (*1972), Giorgio Sommer (1834–1914), Valentin Sonnenschein (1749–1828), Otto Speckter (1807–1871), Thomas Struth (*1954), Johann Georg Trautmann (1713–1769), Gillis van Valckenborch (1570–1622), Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750–1819), VALIE EXPORT (*1940), Dirck Jacobsz. Vellert (um 1480/85 – um 1547), Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), Simon Jacobsz. de Vlieger (um 1601 – 1653), Pierre-Jacques Volaire (1729–1799), Marten de Vos (1532–1603/04), Georg Wasner (*1973), Adam Willaerts (1577–1664), Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), Wilhelm Friedrich Wulff (1808-1882), Michael Wutky (1739–1823)

Mythical Catastrophes

Before 1800 artists would almost always revert to biblical narratives or themes from classical mythology for the depiction of apocalyptic scenarios or natural disasters. According to Christian interpretation, the eruption of elemental natural forces is an expression of divine anger as a punishment of human misbehaviour. These salvation-historical and mythical scenarios are supported by individual heroes: Noah and his family are the only ones to survive the great deluge, Aeneas can escape the burning Troy. After 1800 the attention rather lies on anonymous figures whose despair affects the viewer immediately. This pictorial quality forms one of the fundamental conditions of the modern disaster image.

Friedrich von Rohde (Lebensdaten unbekannt): Die Sintflut, 1841, Öl auf Leinwand, 99 x 129 cm, © Hamburger Kunsthalle

Elemental Forces and Documentation

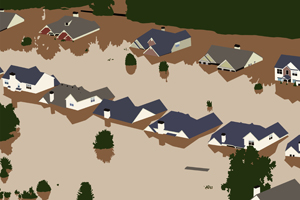

According to the ideas of Antiquity, nature and all that exists consists of the four elements fire, water, earth and air. In the course of the 17th century, this concept of nature is supplemented by portrayals of events that actually occurred: floods, conflagrations, explosions and other calamities. In artists’ reactions to such incidents of their own time tension became apparent between given artistic expectations, the genuine staging of reality and a documentary intent – conflicting priorities which continue to influence artistic production until today. With paintings from the 17th century artworks of our times have in common that they are often based on reports from eyewitnesses or experiences made on site. In our times real catastrophic events are perceived mainly via reports in the media. The fact that information and images are at all times accessible is also reflected in the artistic discourse.

left: Jan Asselijn (1610–1652): Bruch des St. Anthonisdeichs nahe Amsterdam 1651, 1651, Öl auf Leinwand, 85,5 x 108,2 cm © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

right: Kota Ezawa (*1969): Flood, 2011 (Flut), Leuchtkasten, 100 x 150 cm © Courtesy the artist and Galerie Anita Beckers, Frankfurt a.M.

The Turningpoint – Catastrophes as the New Myth

The term »catastrophe« comes from the ancient Greek tragedy and was inseparably connected to it up until the 18th century. It originally referred to the turning point or disastrous finish of a drama. At the beginning of the Enlightenment this concept was extended to include natural disasters and historical events. Depictions of natural disasters were understood in a figurative sense as societal disruptions. Before this backdrop new myths could develop: The earthquake of Lisbon in 1755 is still considered as a turning point marking the transition from the old Christian order towards the Age of Enlightenment.

Anonym: Erdbeben in Lissabon 1755, um 1760, Kupferstich und Radierung, 18,2 x 21 cm, Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg

Eruptions

In the late 18th century, volcanos a central object of study for the natural sciences, as they promised to provide information about the origins of the earth. At the same time Vesuvius quickly became a very popular motif in the art world. Especially it’s eruption in AD 79, which buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under masses of lava. This event had been known for a long time based on ancient sources, but it was presumably the first excavations of those cities during the eighteenth century that made this theme a central motif of the arts. These compositions are directly connected to the aesthetic of the sublime: They were to captivate viewers by means of scarily beautiful motifs at a safe distance to enable them to experience the greatness and power of nature.

Wutky (1739–1822): Vesuv-Ausbruch, um 1796: Öl auf Leinwand, 137,1 x 120,5 cm, Kunstmuseum Basel © Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Bühler

Tremors

Earthquakes vary in intensity. Often we do not even perceive smaller tremors. The long-term consequences of tectonic shifts are not evident to us at first glance. Sometimes, however, they can develop such force that they raze entire cities and regions, destroying thousands of human lives and the very basis for our existence. In terms of time, art depicts the moment of the catastrophe itself but also illustrates its aftereffects. The depictions can seek to document. Often, however, they record the damages abstractly. Several works employ emotional strategies by placing human suffering in the foreground. VALIE EXPORTS spatial installation uses a press photo showing mourning women after an earthquake in India.

VALIE EXPORT (*1949): Red. Date: 1993o93oKillari Village, 1994, 4-teiliger Jetprint auf PCV-Netz, Metallrahmen, Courtesy of the artist

Conflagrations

Fires have always had an Particular influence on human lives. They are not, however, found as an autonomous subject in art until around 1600. That situation changed over the course of the seventeenth century. Gradually, especially in the Netherlands, this everyday reality found its way into art. Scenes of fires, known as brandjes, became a popular theme. Apart from a new exceptions, these works do not, however, depict specific events. Usually they are unspecific fires that cannot be more precisely identified, often combined with a nocturnal scene. Several artists specialized in this subject in order to demonstrate their mastery of effective rendering of the lightning effects at night.

Egbert Lievensz. van der Poel (1621-1664): Nächtliche Feuersbrunst mit löschenden Dorfbewohnern, um 1669, Öl auf Holz, 46.5 x 63 cm, Museumsquartier Osnabrück, Kulturgeschichtliches Museum, Sammlung Gustav Stüve

Hamburg is burning

From 5 to 8 May 1842, Hamburg was ravaged by an enormous blaze. The flames destroyed a third of Hamburg’s inner city with houses, churches and public buildings. Twenty thousand people were homeless as a result of this inferno. A number of depictions of this once-in-a-century catastrophe came onto the market, which testifies to the enormous demands for such products. It is significant that the damage to the city caused by fire was recorded not only in the form of paintings, drawings, and prints but also already using the photographic technique of the daguerreotype, which had been invented just three years earlier. The surviving works are among the first in the world that document such a catastrophe.

Jacob Gensler (1808–1845): Hamburg nach dem Brande von 1842, 1842, Öl auf Mahagoniholz, 45,2 x 52,9 cm © Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk, Foto: Elke Walford

Genre Discovers the Disaster

The development from Romanticism to Realism in German painting during the 19th century was influenced to a great extent by artistic positions from the Düsseldorf School of Painting. This influential art academy, founded in 1819, also engaged in revitalizing the art form of genre painting from the second third of the century on. The historical painting was seen as the highest-ranking genre until then. It now was the tragic fates in the lives of ordinary people and the rural population that increasingly became the subject of ambitious compositions. Via gestures and postures, references to Christian art were sought deliberately. What our busy eyes today may perceive as overly sentimental and emotional, audiences at the time considered as quite realistic and taken straight from life. The representatives of the Düsseldorf School in the mid-19th century had their fingers right on the pulse of the time.

Jakob Becker(1810-1872): Das Gewitter, 1841, Öl auf Leinwand, 39x52cm, Stiftung Sammlung Volmer, Wuppertal

Shipwrecks I

Seafaring was always associated with danger. This is also illustrated by the various shipwrecks in paintings from the 18th century, occurring time and again at cliff coasts with a somehow foreign appearance. Others had attributed a role to the viewer, who longed for intensive emotions when facing a picture and wanted to be deeply affected by it. Overwhelming natural phenomena and human catastrophes, watched from a safe distance, would give the viewer a chill. In addition to volcano eruptions, shipwrecks were considered as the favoured motifs for producing sublime effects in art in the late 18th century.

Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789): Der Schiffbruch, 1762, Öl auf Leinwand, 40 x 31 cm © Musées d’art et d’histoire, Legs, Gustave Revilliod, Genf

Shipwrecks II

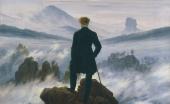

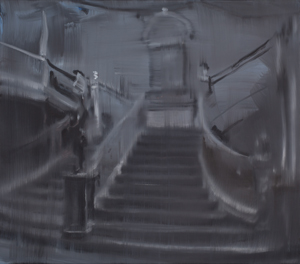

In the Romantic era shipwrecks were remarkably often chosen as subjects of paintings. They serve to illustrate the superiority and vastness of nature, in the face of which humanity is bound to fail – despite its advanced technologies. But shipwrecks that had actually happened would generally not be reflected in the art of this period. But in the course of the 19th century real maritime disasters were met with an unusually broad response in the media of those times and reported in great detail on the course of events of the accident, on the survivors and their rescuers. Artists drew on this source material and increasingly rendered it in particularly dramatic character and monumental formats. With the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, the myth of the unsinkable ocean liner was deeply shaken – with reverberating effects until today.

Uta Schotten (*1972): O.T., 2017, Öl und Enkaustik auf Leinwand, 70 x 80 cm, Privatbesitz, Courtesy the artist © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

The Raft of the Medusa: Géricault and the Consequences

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault, now in the Louvre, is based on an eyewitness report by two survivors of a catastrophic shipwreck. In 1816, the French frigate Méduse ran aground while en route to Senegal. Because there were few lifeboats, a raft was built with room for nearly 150 people. During the process of towing it, the rope was cut off by those aboard the dinghies and the crew was left to fend for itself. After twelve days on the open sea in a life-or-death struggle only fifteen survived until the helping ship arrived. Painting such a political scandal was at once a novelty and a provocation. For that reason, the painting has had an intense reception from the outset. Contemporaneous artists took up various aspects inherent in the original. The approaches of the works presented here range from self-question in the sense of grappling with one’s own mortality by way of reflections on the status of the image as medium and reflections on canonisation of art to complexes of current themes such as exclusion, power and guilt.

Christian Jankowski(*1968): Neue Malerei – Géricault, 2016, Öl auf Leinwand, 491 x 716 cm, Courtesy of the artist and CFA, Berlin

The Last Days

During the years around 1800, the image of the world became gloomier for a time, in the arts as well. A striking large number of works were produced concerning the end of the world and hence of humanity. Whereas in earlier centuries such ideas drew primarily on the Bible, the Romantic visions of decline were more loosely connected to the Christian religion. One consequence of that is that the human being could no longer count on God’s support.

In our day, we can observe once again a turn toward these fundamental questions. Terrorism, wars, natural catastrophes and cosmic phenomena are perceived as threats and immediately linked to knowledge about the finitude of the earth and of our existence. In literature, the fine arts and especially in the medium of film, we find diverse approaches to the theme of the decline of the world and the figure of the last human being. The new element, indebted to the supposedly advanced state of our civilisation, is that the people themselves threaten the earth’s future through their active misbehaviour.

Christoph Draeger (1965): The Rd., 2013, synchronized two-channel video installation, 7:48 Min., Courtesy of the artist

Audioguide

| Description | Audio |

|---|---|

| JEAN-BAPTISTE REGNAULT (1754-1829) Die Sintflut, 1789 | |

| VALIE EXPORT (*1940) Rec Date: 1993o93oKillari Village, 1994 | |

| JACOB GENSLER (1808–1845) Hamburg nach dem Brande von 1842, 1842 |